Text & Photo: Seb Carayol

Special thanks to Kris Kemist and M. Ainley

“The most boring city in England.” While not quite desirable, it’s a title that Luton often wins, according to a certain magazine for modern men, not to forget that the city’s main attraction remains, for hordes of cheap Euro travelers, its low-cost airport. And yet Luton has become home to a legendary character from the English sound system scene, who took refuge there in 1992. His name is Robert “Ribs” Fearon, a former selector for Fatman Hi Fi who proceeded to become the king of the early digital years in England, thanks to its Unity Sound and label of the same name. “Pick a Sound,” “We Try,” “Negative Conquer Positive,” “Ride the Rhythm,” “Watch How the People Dancing” – over 60 cult singles, some of which were reissued in 2003 by Honest Jon’s on its compilation, Unity Sounds from the London Dancehall 1986-1989. Part of the ever-surviving cult lies also in the fact that the elusive Fearon has barely been seen since this golden age, building his own legend brick by brick, using elusiveness as mortar.

It took two years for this interview to happen after a first missed meeting.

Inside the Luton Railway Tavern, one of the few bright lights in the local night, the TVs blaze police car chases, a lovely welcome considering the city’s reputation. Ribs is late. Is he going to skip again? But then, a car horn, outside. A small man with a cap opens the door to his car, smiling, « come in ». As it was, we’re headed to the local BBC 4 studio where Ribs has been co-presenting a Jamaican music show for a few weeks with Lloyd, who is turning him back to music via Gyptian, Chezidek, and Tarrus Riley. Ribs is respected but remains witty and playful, always happy to recall the time when “you knew if someone was a part of Unity because they had seven or eight chains around their neck.”

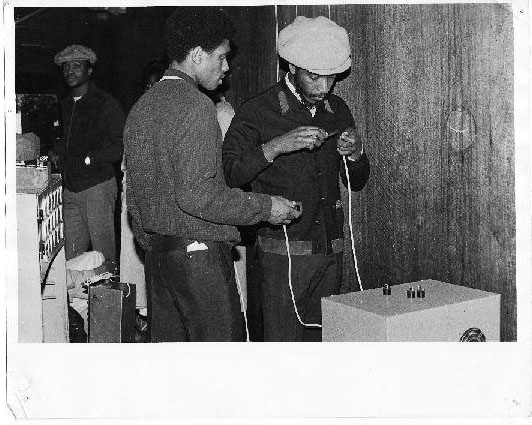

Once the show’s over, Ribs is ready to rewind – to Unity’s humble beginnings. In 1962, Robert and his brother joined their parents in London’s Kentish Town. Their father, a music lover who worked on the railways, had no idea that his boys would go out at night to hear sound systems. “We followed Sir Fanso The Tropical Downbeat,” says Ribs. “One evening, we went to see him at the 77 Club on Holloway Road. At the end of the night, we asked if he could take us in his van and drop us on the way. We asked him every week until we figured where he was coming from. Then we began to show up before the night to help him load… that’s how we became part of his sound.”

From there, Ribs graduated step by step: from box boy to cable helper to disc sleeve holder to warm-up selector – in that order.

After two years, Fanso returned to Jamaica and took his equipment with him. Ribs was 16 years old and put his energy back into “chasing girls.” Six months later, one of Fanso’s DJs, by the name of Fatman, had built his own sound and was becoming the hot new name in north London. One evening in 1972, Ribs joined him at a private blues party in Hackney. “He needed people,” recalls Ribs. “He asked me to help him and to select. I accepted.” The next day, a young Ribs showed up at Fatman’s to “study his record box.” After all, if you’re going to be the selector for the master, you better know all his selections. “Everyone had their own way of marking white label 7”s,” while still never writing the real title to keep it secret. “I’d write ‘very good,’ or ‘excellent,’ or… ‘don’t play’.”

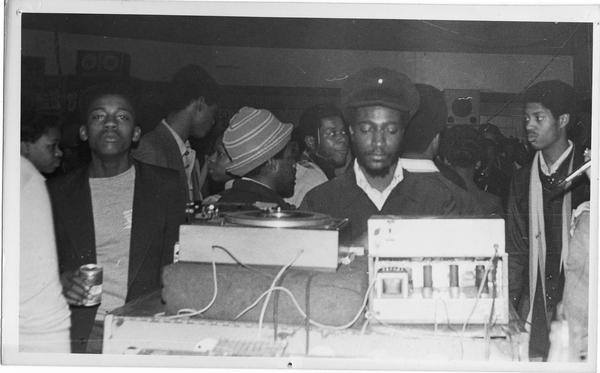

A few years of blues parties pushed Fatman Hi Fi into the lion’s den, to the clubs but also the first clashes, circa 1976. “The first one I saw in London was Coxsone vs. Neville the Musical Enchanter vs. Duke Reid,” recalls Ribs. “Wicked, wicked, wicked! Coxsone had the best music, Neville the power, and Reid was in between. For me, it was Coxsone that won that night.”

The young selector found the game interesting. He put all his energy in clashing and won five titles around 1978 with Fatman. Best memories? “Acton Hall, Fatman vs. Moa Anbessa, King Tropical, and Coxsone. The judges, Prince Jazzbo and Count Shelley, decided to announce the results backwards. When they got to the second, Moa Anbessa, that meant we had won. But the guys from Anbessa didn’t like it and they got on stage and stole the trophy and never gave it back,” Ribs recalls with a laugh. “The organizers had to get us another one.”

To get this kind of win, you need ammunition. Fatman got his dubplates directly from his friend Bunny Lee, as well as from King Tubby. And it’s Tubby that would eventually and unknowingly bring him down – by introducing his student, Prince Jammy, to Ribs. “After staying with Fatman, Jammy ended up at my place and we became friends. I only really thought about music but I was starting to have children, mouths to feed, and Fatman didn’t really share his fees. Jammy and Bunny Lee told me I should build my own sound. So I did.” Ribs began all over again. Luckily, his partner had an uncle, Sir D, whose system was gathering dust in a garage. Ribs added four new boxes, thanks to the skills Fatman, an ex-carpenter, had taught him, and in July 1982 Unity Sound was born, ready to launch its assault on a decade that would bear its mark.

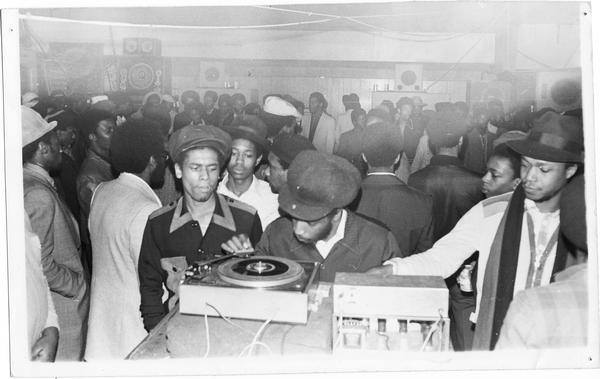

“At first it was just me and my brother and an old selector from Sir D. Fatman had become too big so we took over the blues parties because there wasn’t anybody in the neighborhood anymore.” A year and a half later, having paid its dues, Unity was ready to clash. “The first was against Dennis Bovell’s sound, Sufferer, at the Metro Club. He was a resident there, and so he knew exactly where to put his speakers. But we had an attitude, we were arrogant, we’d jump in the car the second a record shop called us to say they had pre-releases. We busted them!” The first of many wins. With the advent of dubplates, Ribs had a leg up on everyone else. His friend Prince Jammy gave him exclusive productions. “Johnny Osbourne, Junior Reid, Frankie Jones, Leroy Smart.” These were for starters. Jammy hadn’t yet started the digital revolution with his Sleng Teng riddim. As it turns out, the riddim is linked to the “most boring city in England.” “I drove Jammy to a shop in Luton where he bought the eight-track and mixer on which he ended up making Sleng Teng.” Thanks to Steely & Clevie, Prince Jammy became king and gave Unity the necessary grip to control the dances in England. “If you didn’t play Jammy in the 80s, you might as well have not been playing anything,” remembers Ribs. Going even further, Unity became the first English sound to record a named special, just as they did in Jamaica. “Superblack attacked Fatman, Java, Coxsone, and Saxon on our special. We began to play the tune… everywhere!”

From the get-go, Ribs had in mind the idea of releasing singles. He had already tried it, on the proto-labels CF and KG Imperial, and Unity had by then around ten deejays and gifted singers. “The first one to join us was Charjan, who worked with Sir D. He introduced us to his brother, Jack Rubin. Who introduced us to his friend, Demon Rockers. Who introduced us to his twin, Flinty Badman. And so on…” At first, Ribs would get riddims from Jammy and Bunny Lee. “They would come to sell their tunes to labels in London and those left behind – when they were good – I would tell them to give them to me so I could release them locally and see how it went.” This is how we ended up with “Baby Be True” by Junior Delgado, “Put It By Number One” by Johnny Osbourne, and “Back Off We Rule” by Leroy Smart. Sometimes Ribs would only get instrumentals upon which he recorded strictly locals, like Errol Bellot with “Take Warning.”

Eventually, Ribs decided to create his own music, thanks to his engineers Red Eye and Ruddy. Timing? Perfect: Jammy was becoming more and more occupied with Greensleeves anyway.

The first 100% local effort was “Iron Lady” by Demon Rockers, released in 1984. It didn’t do much. The next one, however… “Watch How The People Dancing,” by Kenny Knots, put Unity at the top of the charts in 1986 with an estimated 10,000 records sold. Same again with “Control The Dancehall” by Peter Bouncer, which was, in fact, the same instrumental played in a different key. This was a digital sound to chop up dancehalls, yet still rugged and homemade. You could often hear the metronome from the Simmons electronic kit in the tracks, a sharp “blip” that became an integral part of the tunes. Still, the sound worked. “Pick a Sound” by Selah Collins hit big, Richie Davis preferred Kangol to “Lean Boots,” the mood was for lyrics about war and party but never rude. Many of the singers introduced by Unity have continued to work to this day: Kenny Knots, Mikey Murka, Selah Collins, Errol Bellot. Others took different paths. Speccy Navigator took a hard electro turn, while the twins Flinty Badman and Demon Rockers became the iconic jungle duo Ragga Twins whose debut album Reggae Owes Me Money perhaps said it best.

Despite these successes, the start of the 90s was the beginning of the end. “I lost interest in music from Jamaica,” explains Ribs. “The dancehall scene became this thing where it was lyrics for women. Wicked inna bed? You can keep waiting for me to play that. And sounds started to have two turntables, you’d end up hearing the same song three or four times in one night, something you’d never do in my time. I took some time to concentrate on production and I moved to Luton and left my brother as selector.”

One by one, the singers also left. “No one really left, it was more Unity had less and less steam,” not to mention the occasional feud, explains Errol Bellot. As for Ribs, he has no regrets. “If you work hard you might get lucky and become a selector for a sound system that left a mark. That happened twice for me, with Fatman and then Unity.” Enough for a couple lives. And it’s lucky too – apparently in Luton, there’s only really memories to pass the time.